–

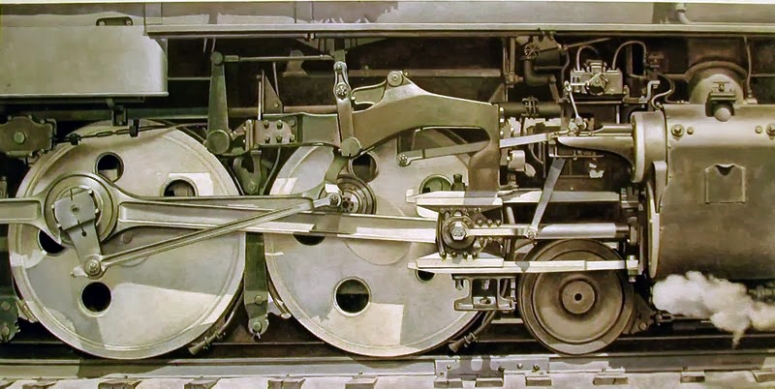

(Yes, this oil painting does look like a very good photograph (in 1939) of some locomotive’s wheels and connecting rods. It is kept in the Smith College Museum of Art at Northampton, MA, and is deservedly famous. Along with other oils and crayon-drawings in a similar line, it inaugurated a new style in painting –Precisionism, as it was called; one of most peculiar tendencies within Modernism in the USA.)

–

Charles Rettrew Sheeler (Philadelphia, 1883 – Dobbs Ferry, NY, 1965) expressed himself artistically through photography, painting, drawing, etching and also cinematography. He excelled in each of these media, and moreover, he established between them a tight connection, very infrequent until then. (I could have called him “Photopaintdrawer” as well, but “Paintdrawgrapher” sounded to me more accurate, and also more euphonic.)

Here down there are some other examples of this feedback between arts -now between photography and drawing:

- A photograph:

–

- A pencil drawing:

–

- A photograph and a pencil drawing:

–

- Another (surprising) pencil drawing -illustrating the basement of the same house as the previous picture and drawing:

–

(The Stove and Open Door were photographed in Doylestown House, at the Bucks County, Pennsylvania; the home that Charles Sheeler shared with fellow painter and photographer Morton Schamberg, and drawn some fifteen years later. The exquisite range of tones and textures achieved solely with black Conté crayon attests to Sheeler’s mastery of the medium, which, he noted, was used “to see how much exactitude I could attain.”)

–

Sheeler’s first and dearest dedication was photography, which in his youth and mid-age (in the 1920s and 1930s) had not yet attained status as a major art, on an equal footing with the more classical ones. That medium was, in my opinion, the one he always loved more and the one that determined his entire later work.

In particular, both for personal preference and in order to earn a living, he photographed mainly factories and diverse machinery (but also quite a few barns and silos). And from many of the excellent pictures taken, he drew inspiration for crayon drawings and oil, tempera or watercolour paintings.

I have not found any prior photo for the oil named “City Interior”, from 1936 -depicting a corner of the huge Ford factory-, but surely they exist; it would be interesting to compare them with the oil, but anyway, they would hardly show more details than it:

–

–

Reciprocally, in return to the inspiration he was getting from the photos, and having been captivated by the cubist painting of Picasso and Braque in the 1920s, Sheeler sought to attain images as “cubist” as possible with the camera; either directly, through some peculiar framing of the motives or overlapping and combining two or more negatives in a single image -or both ways at once-. The great picture “Criss-Crossed Conveyors”, shot in the Ford Plant at River Rouge, in 1927, and “Upper Deck”, from 1928, are proper instances of the first alternative:

–

–

–

–

A year later, Sheeler would use Upper Deck as a basis for an oil with the same title. From then on, practically everything (if not absolutely everything) beautiful and innovative he created with painting and drawing, he had seen it first through the objective of a camera, and, of course, conscientiously photographed it.

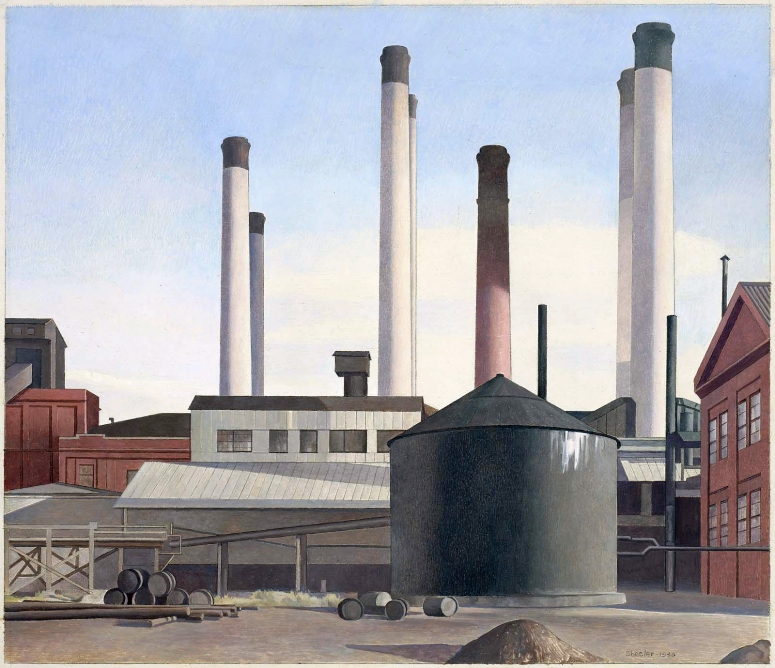

In an increasingly mechanized world, a balance between abstraction and representation, photography and painting, was difficult to achieve, but he did it very well. We may notice this looking at the following views of the electric power plant at New Bedford, MA: first, a photograph and after, a coloured drawing from 1940 (which is one of my favourite works by him):

–

–

–

–

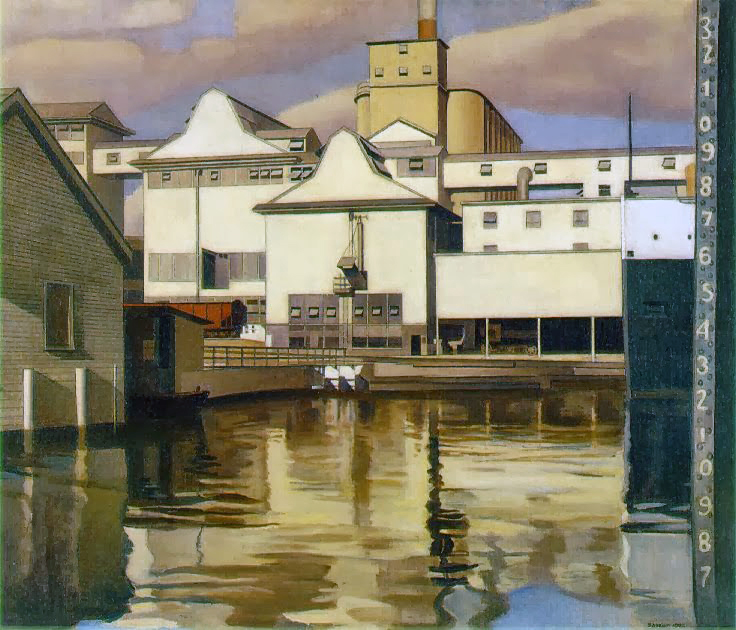

In the same clean, clear and elegant line, I also like much “American Landscape”, “River Rouge Plant” and “Bucks County Barn”:

–

–

–

–

–

–

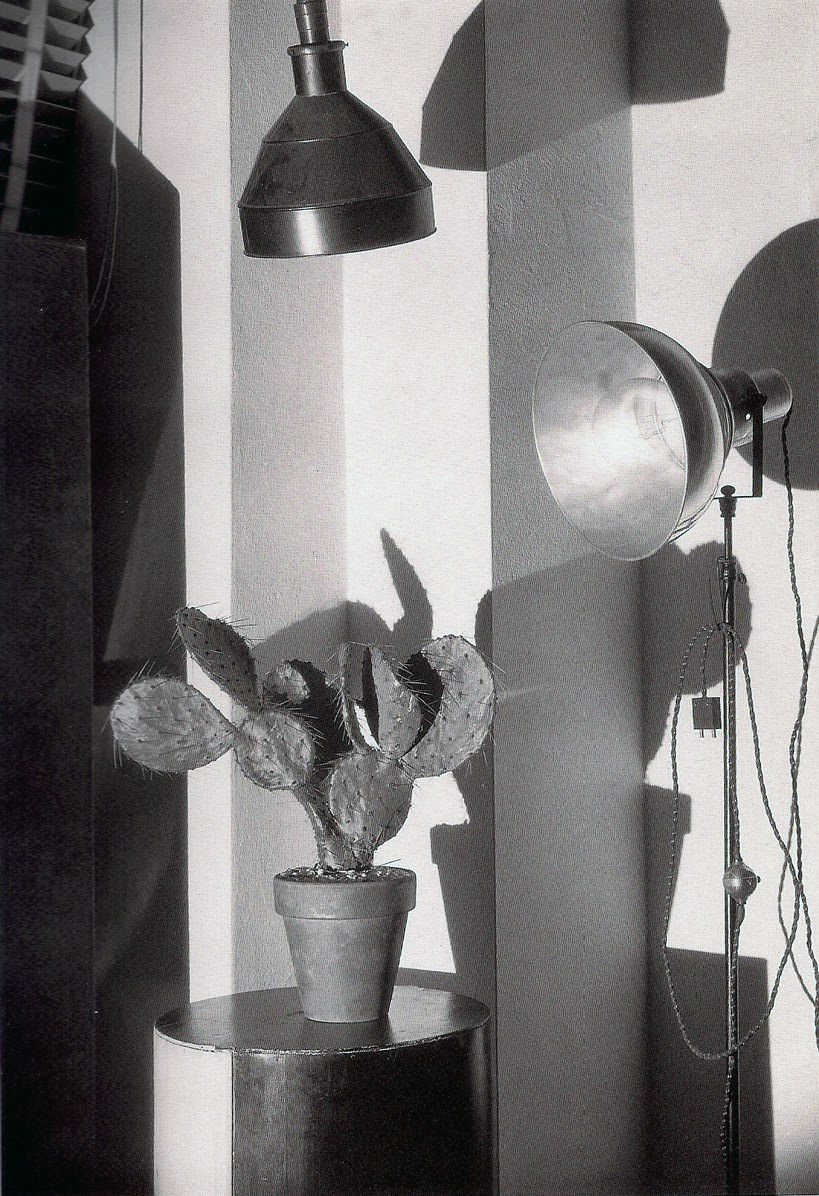

With respect to the interiors (again in the artist’s home, but now at South Salem, NY), look at these two splendid oils and a watercolour on a black crayon drawing, all from 1931. (I pair the second oil, “View of New York”, with “Cactus and Photographer’s Lamp” -also from the same year- in order to keep on showing the principal, decisive role that photography had for this versatile artist. Perhaps it would be needless to point out that the “view of New York” alluded in the title of the painting might be (or might have been), most probably, inside that ancient camera covered with a black veil.)

–

–

During years, Charles Sheeler exhibited the photos along with the paintings indicating the belief that his work in each medium shared the same status, but at the same time, with its own merit and own entity. Nevertheless, some critics used to judge the paintings with a certain indifference or even disdain, calling them subsidiaries; simple replicas or variations made in oil or pencils -very well done, indeed, but devoid of artistic content-. This, false and unfair as it was, affected Sheeler, who gave up doing joint exhibitions and began to modify his painting style, abandoning the eagerness of precision which had motivated him so much (and so well). Since the mid 40s, he painted works that, even though continuing to illustrate his usual subjects (industries, buildings, major engineering works), are more abstract and fancifully lightened and coloured; and the remaining cubist features -left, earlier on, to framing, cropping and composition- become more freely and directly depicted.

I will show a selection of the late works in a second article, but to end this one -which is already long enough!- and link rightly with the follow-up, I attach now here down a sort of transitional work; or perhaps better said: a final work of a period, since it still keeps a certain air of Photorealism an Precisionism.

–

–

–

Index, with all data I can provide, of each work displayed in the post:

- Rolling Power (1939 – oil on canvas, 38.1 x 76.2 cm) – Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, MA.

- Blast Furnace and Dust Catcher, Ford Plant (1927 – photo: gelatine silver print) – Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- Ballet Mechanique (1931 – black Contè crayon on paper, 25.4 x 26.7 cm) – Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester.

- The Stove (1917, photo: gelatine silver print, 23.1 x 16.3 cm) –

- The Stove [Interior with Stove] (1932 – black Conté crayon on paper, 71,1 x 53.3 cm) – National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- Open Door (1932 – black Conté crayon on paper, 60.3 x 45.7 cm) – Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

- City Interior (1936 – oil on gessoed panel – 55.9 x 68.6 cm) – Worcester Art Museum, Worcester.

- Criss-Crossed Conveyors, River Rouge Plant, Ford Motor Company (1927 – photo: gelatine silver print, 23.5 x 18.8 cm) – Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

- Upper Deck (1928-1929 – photo: gelatine silver print, 25.3 x 20.2 cm) – Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

- Electric Power Plant, New Bedford, MA (photo: gelatine silver print) –

- Fugue (1940 – tempera and graphite on gessoed masonite, 35.6 x 43.2 cm) – Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- American Landscape (1930 – oil on canvas, 59.7 x 77.5 cm) – Museum of Modern Art, New York City.

- River Rouge Plant (1932 – oil on canvas, 51 x 61 cm) – Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City.

- Bucks County Barn (1940 – oil on gessoed panel, 46.7 x 72.1 cm) – Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago.

- Americana (1931 – oil on canvas, 122 x 91.5) – Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

- Home, Sweet Home (1931 – watercolour and black Conté crayon, 91.4 x 73.7 cm) –

- View of New York (1931 – oil on canvas, 121.3 x 92 cm) – Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- Cactus and Photographer’s Lamp (1931 – photo: gelatine silver print, 23.5 x 16.6 cm) – Museum of Modern Art, New York City.

- Water (1945 – oil on canvas, 61 x 74.3 cm) – Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

–

[You may also read this post in Catalan on my blog at VilaWeb digital journal: – Charles Sheeler – ‘Pintògraf’ de fàbriques i maquinària (Part I)]

–

No unauthorised copying or redistribution. All Rights Reserved.

Amazing!!!! Kodak moments brought to life by pencils and crayons!!!! Excellent work!!!! Thanks for sharing!!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are dearly welcome! Thanks to you for your visits and comments 🙂

Many big, affectionate hugs, John!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hugs back to you, my friend!!!! Always a pleasure to help keep her memory alive in the hearts of those who loved her!!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Crowds at first glance, not many ( few!) in the long term, but all of them very worthy 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just love the eyes 👀 of an angel

LikeLiked by 1 person

+**** of an artist 👨🎤 *****

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hahaha 🙂 Thanks a lot for being here and commenting, Nita!

Best wishes

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey 👋.. I love reading 📖 great stories…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amazing post, Linus. Staggering!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the compliment !

(In fact, having read several of your posts, I thought you could like this one on Sheeler) 🙂

LikeLike

How right you are, Linus! 🙏 How right you are! Incredible images – the pencil and charcoal drawings are just mind boggling! Very interesting subject!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Namaste ! 🙂

I’ll post a second part one of these days, dealing with Sheeler’s later works -where he increasingly derived to abstraction-. I love them as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I look forward to that, Linus. All the best. R

LikeLiked by 1 person